About a year and a half ago I wrote a column in which I said “Fiction is made of sentences.” Though not false, that statement isn’t exactly the truth. Last week a sharp-eyed, if not-up-to-date, reader from Atlanta wrote to correct me. “It’s not the sentence that is the basic building block,” claims Joshua Collins, “but the word. With the wrong words, you can’t build a good sentence.”

And, of course, he’s right.

Words are our raw materials. In any act of creation, the higher quality and better chosen the raw material, the better the result. Words are the atoms out of which your fictional universe is constructed.

So if words are the basis of fiction, the specific words you choose (what’s known as diction) will have a tremendous effect on the quality of your story. Yes, plot and character and setting and all those other things also matter–a lot–but each of those elements comes to your readers only through words. Word choice can turn a good story into a bad one, or vice versa.

So what makes a word choice or a phrase choice (a phrase merely being a clump of words that like to hang around together) “good”? Four things: tone, vividness, consistency and rhythm.

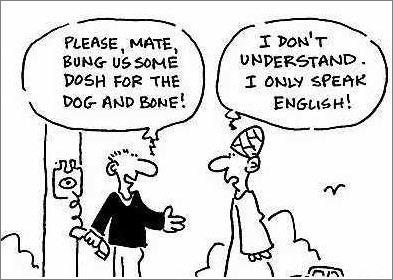

Tone: A Primer on English Words

English is an incredibly rich language. My thesaurus lists 83 words for red, each synonym suggesting a subtly different shade. There are 92 ways to be sad, from the transient out of sorts to the serious heartsick. This richness exists because English is a vacuum cleaner of a language, sucking up words from every people Great Britain ever hosted, was invaded by or got interested in.

English is an incredibly rich language. My thesaurus lists 83 words for red, each synonym suggesting a subtly different shade. There are 92 ways to be sad, from the transient out of sorts to the serious heartsick. This richness exists because English is a vacuum cleaner of a language, sucking up words from every people Great Britain ever hosted, was invaded by or got interested in.

The two main sources of English, however, were Anglo-Saxon and Norman French. The Saxons were the conquered, the serfs, and so their short, brusque words seem to us more earthy and common (including the usual “four-letter words”). The Normans, whose French descended from Latin, had words that sound more formal, refined or even abstract to the modern ear. Thus, William the Conqueror was king to his Saxon subjects, but sovereign to his Norman ones. A meat animal was a cow to the serfs who raised and killed it, but beef to those who mainly dealt with it after it was on the dining table.

Nine and a half centuries later, English words derived from Anglo-Saxon or Norman French still give different effects when used in contemporary fiction. Consider these two sentences:

Julia detested restrictive regulations.

Kate hated “no.”

They suggest quite different women, don’t they? The difference lies not in the meanings of the two sentences, but in their diction, which, in turn, affects tone. Do you want a tone of immediacy, earthiness, visceral feeling for your sentence? Choose predominately Anglo-Saxon words. Do you want a tone of thoughtful, more distant observation? Choose Latinate diction.

To further see the richness of possibility this presents, contrast the tone of this pair of sentences, the first from an author fond of Latinate words, the second from another who is fond of Anglo-Saxon ones:

It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a wife. (Jane Austen, Pride and Prejudice)

Brett was damned good looking. She wore a slipover jersey sweater and a tweed skirt, and her hair was brushed back like a boy’s. She started all that. (Ernest Hemingway, The Sun Also Rises)

And this pair, more contemporary:

I was born in 1927, the only child of middle-class parents, both English, and themselves born in the grotesquely elongated shadow, which they never rose sufficiently above history to leave, of that monstrous dwarf Queen Victoria. (John Fowles, The Magus)

Deer Lick lay on a narrow country road some 90 miles north of Baltimore, and the funeral was scheduled for 10:30 Saturday morning, so Ira figured they should start around 8. This made him grumpy. (Anne Tyler, Breathing Lessons)

English has also absorbed words from many other languages, some of which still lend an exotic feel to prose. Can you hear it in these sentences?

Kalisha wore palazzo pajamas to Susan’s fete.

Kalisha is African, palazzo is Italian, pajamas comes from Arabic, and fete is undigested French.

I schlepped my portfolio around the city. Nada. When I couldn’t stand it anymore, I stopped for curry and angst somewhere on Ninth.

Schlepped is from Yiddish, nada is Spanish, curry is Indian, angst comes from German. And can anyone mistake that this city is New York?

When you choose your words, consider the overall tone they are contributing to your sentence. Is it the tone you want?

Vividness: The Eyeball Kick

Eyeball kick is a term coined by writer William Gibson. It means an image that hits readers’ eyes with a strong visual image perfect for the context. Not just any strong image is an eyeball kick. It goes beyond delivering a picture to delivering a picture sharp and hard with extra meaning. An eyeball kick, like a literal kick in the face, makes a meaningful difference to readers’ perception of a situation. Such words are vivid in context–they tell us more than less vivid synonyms would.

Here is a brief scene written in generic, nonvivid words. The action is all there, but the eyeball kicks are not:

When I walked into John’s house, music was playing on the stereo. John was nowhere to be seen, but that didn’t stop me. Nothing could stop me. I went past the dining room, through the living room, until I found him in the kitchen. “John, I want to talk to you.”

Information is conveyed, but this paragraph lacks vividness. Boredom City. Now read three different versions of the same thing, to see what a difference vivid, specific, carefully chosen, nongeneric diction can make:

When I stormed into Bubba’s trailer, the Carson-Akabar fight was playing on the big-screen Sony. Bubba was nowhere to be seen, but that didn’t stop me. Nothing could stop me. I tore past the beer cans and pizza boxes, racing through the trailer until I found him taking a crap in the can. “You bastard! I’ve got something to give you!”

When I sauntered into Serge’s, “Tosca” was playing on the CD. Serge was nowhere to be seen, but that didn’t stop me. Nothing could stop me. I strolled past the library and the sauna, making my way through the mansion until I found him repotting violets in the conservatory. “You sly dog, I have a message for you.”

When I crept into Daddy’s, some old-timey music was playing on the radio. Daddy was nowhere to be seen, but that didn’t stop me. Nothing could stop me. I sneaked past all the woman’s clothes on the living room floor and the closed bedroom door, tiptoeing through the house until I found him in the garage. “You… Daddy, listen, I’ve got to tell you something.”

It’s all in the diction. Think vivid.

Consistency: Words of a Feather

But if you make full and exuberant use of the rich range of tone and diction available in English, won’t your style seem fragmented? As if you had contracted a multiple personality disorder, sounding on page 14 like a 12-year-old peasant, on page 27 like a professor, on page 43 like a wealthy socialite educated abroad? What about consistency? Doesn’t prose have to sound consistent?

Yes and no.

Certainly the various scenes of a novel should sound as if they all belong in the same book, written by the same person. But depending on how your book is structured, you may have more choices in diction than you think.

A multiple-viewpoint novel, for instance, may vary the diction quite a bit from scene to scene, depending on switches in POV character. You already do that, of course, for dialogue: Your characters don’t all talk alike. Some use age-appropriate slang, some have better vocabularies than others, some are stiff and cautious in their speech, some try to impress, some curse more, some have a regional or ethnic accent, some have more (or less) correct grammar, some are observant, some are not. In a novel written in close multiple-third-person point of view, these same differences can also show up in the narrative sections. This means the diction may vary between sections.

Can you see the difference in word choice between the first passage below and the second? Both come from my thriller Oaths and Miracles:

A man waited in Felders’s office. Younger than Cavanaugh: 25, 27. Expensive dark gray suit, rep tie, Ivy League haircut, a certain self-conscious precise look that Cavanaugh recognized instantly. A new Justice attorney, trying to look older and more important than he actually was. Hired after spring graduation, they bloomed in August, like ragweed.

The prayer just sort of mistook him–he didn’t know he was going to say it until it was too late and the prayer was out. Wendell scowled and spat on the ground. His praying days were over, that was for damn sure. He’d prayed and prayed, and where the fuck had it got him?

The first paragraph is from the POV of FBI agent Robert Cavanaugh, and uses words that reflect his range of knowledge (“Ivy League haircut”), directness (verbs left out, Anglo-Saxon words), linguistic sophistication (the metaphor “bloomed in August, like ragweed”). The narrator of the second paragraph, ex-convict and all-around-loser Wendell Botts, also favors Anglo-Saxon words, but his diction is less precise (“just sort of mistook him”), more repetitious (“prayed and prayed”), cruder (“spat,” “damn sure,” “fuck”), and without anything as poetic as a metaphor. The diction changes as the POV character does.

At the same time, there is enough consistency in diction to easily see that these two passages could come from the same novel. However, the two passages I quoted from Austen and Hemingway, could not. The diction is too different.

Your word choices should be fairly consistent. At the same time, a multiple POV does give you some room to contrast diction in narrative as well as dialogue.

Leave a Reply